“There has risen fr om the sea a beast, full of words of blasphemy, which, formed with the feet of a bear, the mouth of a raging lion, and, as it were, a panther in its other limbs, opens its mouth in blasphemies against God’s name, and continually attacks with similar weapons his tabernacle, and the saints who dwell in heaven.”

om the sea a beast, full of words of blasphemy, which, formed with the feet of a bear, the mouth of a raging lion, and, as it were, a panther in its other limbs, opens its mouth in blasphemies against God’s name, and continually attacks with similar weapons his tabernacle, and the saints who dwell in heaven.”

With these words, written in a 1239 encyclical, Pope Gregory IX assaulted the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220-1250), with whom he was repeatedly engaged in territorial conflicts. Vexed by Frederick’s wars against the Papal States, Gregory excommunicated him twice – once in 1227, again in 1239 – and compared him to the antichrist. The language in the encyclical, which was sent to kings and bishops throughout Europe, evokes the image of the blaspheming sea beast from Revelation 13. Frederick responded in kind, calling Gregory “that great dragon, who deceives the whole world” and “the prince of darkness who misquotes prophecy, who misstates the Word of God.”

Literature

• David Abulafia, Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor (London 1988)

• Peter Segl, ‘Die Feindbilder in der politischen Propaganda Friedrichs II. und seiner Gegner’, in: Franz Bosbach (ed.), Feindbilder. Die Darstellung des Gegners in der politischen Publizistik des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit(Cologne – Weimar – Vienna 1992) 41-71

• Richard F. Kassady, The Emperor and the Saint: Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, Francis of Assissi, and Journeys to Medieval Places (DeKalb, IL 2011)

1193) was feared and admired by his Western opponents. Both in literary and visual media, he appeared as an incarnation of the antichrist or as one of the seven heads of the dragon from the Book of Revelation. However, there was also room for a positive tradition, in which Saladin was allegedly baptized before his death. Thus it was attempted to incorporate this respected opponent in the Christian world order.

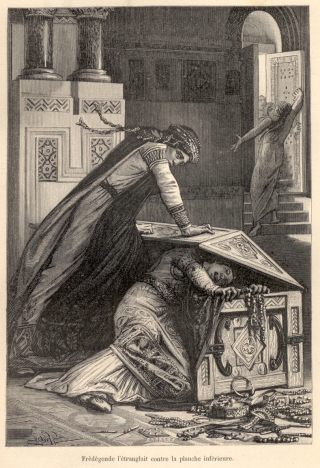

1193) was feared and admired by his Western opponents. Both in literary and visual media, he appeared as an incarnation of the antichrist or as one of the seven heads of the dragon from the Book of Revelation. However, there was also room for a positive tradition, in which Saladin was allegedly baptized before his death. Thus it was attempted to incorporate this respected opponent in the Christian world order. Long is the list of crimes that bishop Gregory of Tours lays at the feet of the Merovingian queen Fredegund (d. 597) in his

Long is the list of crimes that bishop Gregory of Tours lays at the feet of the Merovingian queen Fredegund (d. 597) in his